door Richard Wolfe, DVS

English version below! Follow this link.

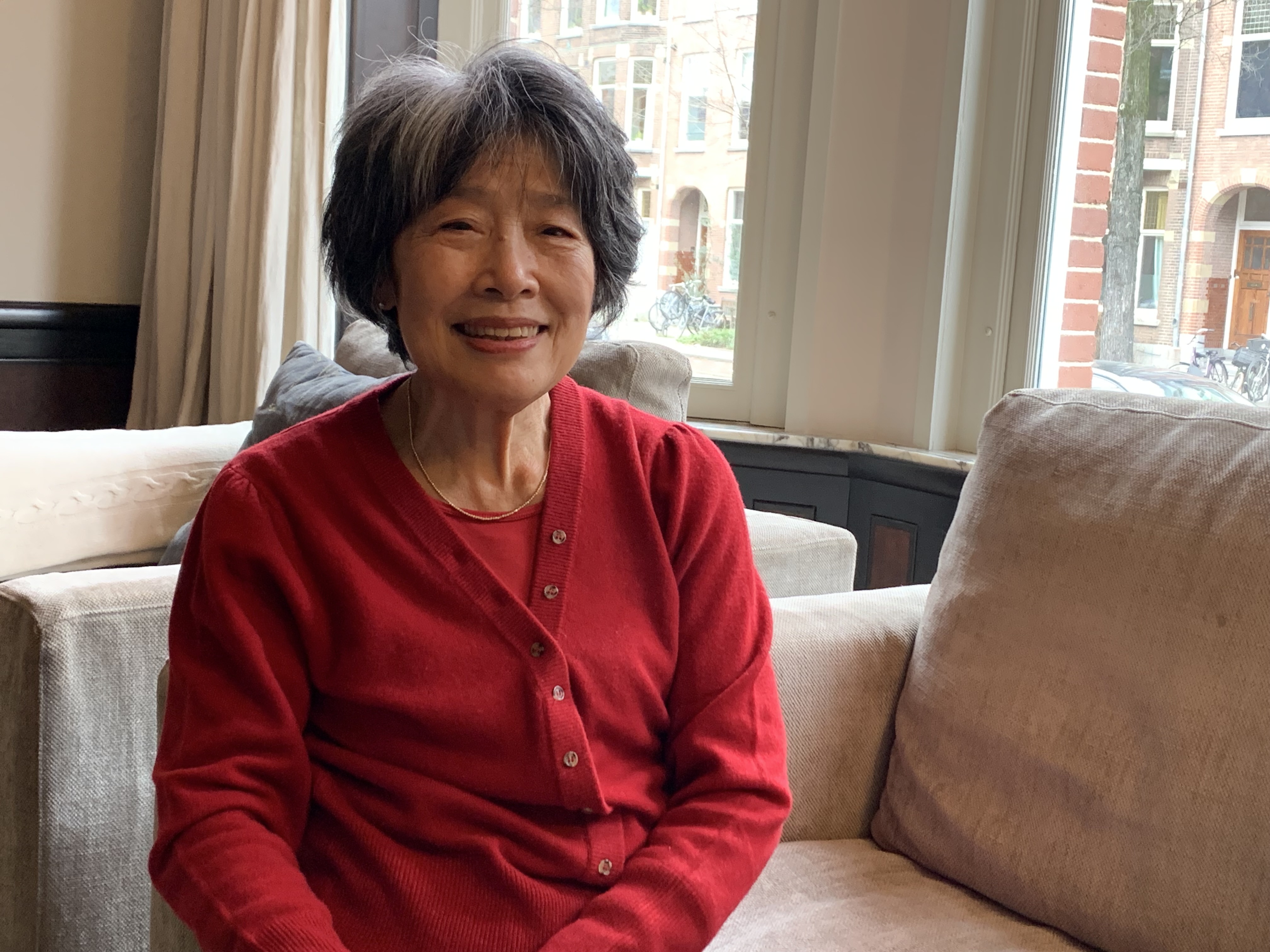

Ik word door Hans Neuburger en zijn vrouw Sonja ontvangen in hun aangename woning in Huizen. Bij een kopje koffie en gebak begint Hans over zijn leven en loopbaan te praten.

Ik ben geboren in 1934. Tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog zijn mijn 5 jaar jongere zusje en ik ondergebracht in een Doopsgezind Kindertehuis in Baarn. Daar waren ook kinderen wiens ouders nog in Nederlands-Indië gebleven waren.

Ik ben geboren in 1934. Tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog zijn mijn 5 jaar jongere zusje en ik ondergebracht in een Doopsgezind Kindertehuis in Baarn. Daar waren ook kinderen wiens ouders nog in Nederlands-Indië gebleven waren.

Ik had daar al vioolles en reisde elke zaterdag met de trein naar Amsterdam voor lessen bij Ferdinand Helmann, concertmeester van het Concertgebouworkest. Mijn ouders bleven in Amsterdam, blijkbaar kon je in zo’n grote stad toch nog anoniem blijven. Vele jaren later hoorde ik het verhaal van een achterneef van mijn vader: Elie Neuburger, kunstschilder, die op zijn atelier 3 hoog op de Snoekjesgracht bleef wonen. De gehele buurt wist ervan en hield zijn mond!

Mijn moeder, die een aardige stem had, heeft toen mijn vader niet kon werken, als amusement musicus, Franse chansons en Duitse liedjes ingestudeerd en gewerkt in de Bar Madrid op het Rokin. De eigenaar van de bar, Heinz Ruf, kwam al na 1933 naar Nederland. Hij had blijkbaar contacten met het verzet, en heeft onze familie veel geholpen.

Een voorval: Tijdens de oorlog kwam er regelmatig een kaalhoofdige man in de bar, dronk een cognac en verdween weer snel. Er werd aan Heinz gevraagd: wie is dat? Waarop Heinz altijd antwoordde: Dat moet je maar niet vragen! Na de oorlog is de bar weer geopend, en de vaste klanten komen terug, waaronder de duistere man; waarop Heinz zegt: Mag ik jullie voorstellen: Max Beckmann! (schilder die met zijn vrouw na toespraak over ‘Entartede Kunst’ gevlucht was, en zijn atelier op de Amstel had. In 1947 is hij naar de V.S. gegaan, waar hij in 1970 is overleden)

Ik heb Vooropleiding en later toelatingsexamen voor het Amsterdams Conservatorium, toen nog aan de Bachstraat. Bij het toelatingsexamen zei de directeur- Willem Andriessen, pianist en broer van Hendrik- dat ik een studiebeurs kon krijgen als ik altviool ging studeren. Vanaf 1951 kwam ik bij Klaas Boon, solo-altist van het Concertgebouworkest. Studierichting: Orkest-Diploma.

Tijdens mijn studie schnabbelde ik regelmatig in diverse amateurorkesten. Ook nog in het Kunstmaand Orkest, de voorloper van het Nederlands Philharmonisch Orkest. De dirigent was Karel Mengelberg, neef van Willem, componist en muziekcriticus van het dagblad Het Vrije Volk en vader van Mischa.

Na mijn studie kreeg mijn vader een baan in Canada. Hij zag geen toekomst meer in Nederland als amusementsmusicus (trompet en accordeon). Onze familie verhuisde eind 1953 naar Winnipeg. Ik heb daar gespeeld in het Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, CBC Winnipeg Radio Orchestra en nog 3 jaar hoorn in een legerorkest.

Na een aantal jaren werd het me te provinciaal, de afstanden in Canada en de V.S. te groot. Gelukkig heb ik wel veel van dat grote land gezien; de uitgestrekte wouden en meren, en de binnen de poolcirkel gelegen Port Arthur. Ook reisde ik van Winnipeg naar een tante in Miami met de Greyhound bus, door beide landen. In 1955 was er nog de segregatie tussen Noord en Zuid van de V.S., en ik was geschokt toen na de Mason-Dixon linie de zwarte mensen plotseling achter in de bus zaten!

Na zes jaar Winnipeg besloot ik terug te gaan naar Nederland, en kreeg ik een baan in de altvioolgroep van Het Brabants Orkest. Ik leerde Ervín Schiffer kennen (bekende altviool pedagoog, in 2014 overleden), die mij aanraadde om te solliciteren in Duitse orkesten.

Uiteindelijk, na een paar mislukte sollicitaties, kreeg ik de post van solo-altist in het Nieder-Sächisches Symfonie Orchester in Hannover. Dit orkest speelde abonnement concerten in Hannover en in kleine theaters in de provincie, zomerconcerten in de Balzaal van het voormalige Slot en tuinen Herrenhausen (met een openluchttheater waar G.F. Händel nog gewerkt heeft). Vaak heb ik Telemann’s altvioolconcert gespeeld, dat was in de kleine theaters makkelijk te programmeren ook zonder klavecimbel.

In 1963 deed ik een auditie in München voor een solo-altviool plaats bij het Symphonie Orchester des Bayerische Rundfunk, en kon toen de 3e plaats krijgen. Een week eerder deed ik ook een proefspel in Hilversum, en kreeg een aanbod om 1e Solo-altist bij het RFO te worden. Mijn toenmalige vrouw en ik vonden het niet zo’n goed idee onze twee kinderen op te laten groeien in Duitsland, en besloten weer naar Nederland te gaan.

Voordat ik in Hilversum begon, ben ik in Hannover van het podium gevallen bij een voor-repetitie. Ik had toen gelukkig alleen en breuk in mijn schouderblad en een lichte kneuzing in mijn rechter schouderkom. De Mozart Symfonie Concertante heb ik toen niet meer kunnen uitvoeren. De breuk genas wel snel, waardoor ik op 15 augustus bij het RFO kon beginnen.

Later heb ik de Concertante twee keer met de concertmeester van het RFO, Dick de Reus, kunnen uitvoeren. Eén keer o.l.v. Jean Fournet, en later nogmaals met Willem van Otterloo.

De eerste maanden in het RFO waren ook een soort proefspel, met de grote orkest-soli: H. Berlioz – “Damnation de Faust”, A. Ginastera – “Variaciones per Orchestra“ op.23, Benjamin Britten – “Passacaglia” uit Peter Grimes, en met Jean Fournet: Berlioz – “Harold en Italie”.

Ik heb van Jean Fournet heel veel geleerd over het Franse repertoire, zoals de verschillen tussen bv. “retenu”, “un peu retenu” en “ritard” en de vanzelfsprekendheid waarmee hij de werken in dit repertoire vorm gaf. Ik heb mij later tijdens concerten verschillende malen zitten ergeren over de slechte uitvoeringen van bv. Fauré – Pelisande en Ravel – La Valse.

Fournet’s slagtechniek was zeer duidelijk en efficiënt, waardoor de “Sacre” (die het RFO al eerder met Fournet had uitgevoerd) niet moeilijk was!

Het werken bij het RFO heb ik altijd boeiend gevonden, met een breed repertoire, van hedendaags tot en met opera en koorwerken. De Zaterdagmiddag Concerten met grote dirigenten; Kondrashin, Giulini, Mazur, Haitink, Hans Vonk en David Zinman – van David kreeg ik de nieuwste Jiddische moppen, die hij weer van Itzhak Perlman kreeg.

Er waren grote solisten zoals: Martha Argerich, Murray Perahia. Earl Wild, J. Bolet en A. Rubinstein. Nog een anekdote: tijdens een voorrepetitie staat Rubinstein in de dirigentenkamer van het Concertgebouw en wij vragen hem: Waarom bent U hier zo vroeg? U heeft vanavond zelf een concert in de Grote Zaal! Antwoord: ik heb Martha (Argerich) al zo lang niet gehoord, dus kom ik even luisteren!

In 1964 werd ik gevraagd als lid van Het Nederlands Hobo Kwartet (Hobo, Viool, Altviool en Cello). Met hen heb ik een aantal radio-opnamen gemaakt en diverse concerten gegeven. Voor een radio-opname kreeg je toen 85 gulden, voor een recital 100 en voor een soloconcert 150!

In 1969 werd ik benaderd door de cellist van het Gaudeamus Kwartet, hun altviolist ging met pensioen. In die jaren hadden zij nog klassieke werken op het repertoire plus moderne werken. 2e en 4e Bartok, 3e Pijper, Ton de Leeuw, Peter Schat, Lutoslavsky, Luciano Berio, Alban Berg, Anton Webern. Dit betekende dat ik vooral in het eerste jaar flink moest studeren naast de orkestpartijen van het RFO. Het Gaudeamus Kwartet heeft concerten gegeven in heel Europa en ook tweemaal in de Salzburger Festspiele.

Verder heb ik 10 jaar lang les gegeven aan het Conservatorium Arnhem: kamermuziek, bijvak altviool en methodiek. Ook heb ik plaats genomen in examencommissies van verschillende conservatoria en in jury’s van jeugdconcoursen en in het Charles Hennen Kamermuziek Concours.

Tot zover het relaas van Hans Neuburger. Ik krijg van Hans 16 prachtige CD’s mee met eigen opnames van solowerken, sonates, en orkestwerken, die hij mij beschikbaar heeft gesteld. De lijst van werken, die ik hieronder met jullie deel, is fascinerend: bekende en minder bekende muziek, maar ook stukken die helemaal uit het altvioolrepertoire zijn verdwenen. Zeer aanbevolen als uitgangspunt voor de ondernemende altviolist!

Tot zover het relaas van Hans Neuburger. Ik krijg van Hans 16 prachtige CD’s mee met eigen opnames van solowerken, sonates, en orkestwerken, die hij mij beschikbaar heeft gesteld. De lijst van werken, die ik hieronder met jullie deel, is fascinerend: bekende en minder bekende muziek, maar ook stukken die helemaal uit het altvioolrepertoire zijn verdwenen. Zeer aanbevolen als uitgangspunt voor de ondernemende altviolist!

Concerti en concertante werken

W.A. Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante K.364 met Dick de Reus, RFO dir. Jean Fournet

en (idem) met dir. W. van Otterloo

Anton Wranitzky: Concert voor 2 altviolen in C met Gerard Vermeulen RFO dir Henk Spruit

Oscar van Hemel: Altvioolconcert, Omroep Orkest dir Henk Spruit

Johann Stamitz: Concerto in C, Kamerorkest P. Hellendaal dir. Henk Spruit

J.Chr. Bach: Concerto per il Pianoforte e Viola obl. in Es, met Rudolf Jansen, RKO dir Paul Hupperts

J.S. Bach: 6e Brandenburgs Concert met Herman Wiegmans, altv; LP, Soester Cantorij dir. Maarten Kooy

H. Berlioz: Harold en Italie, RFO dir. Jean Fournet

Joseph Schubert: Viola Concert in C, RKO dir. P. Hupperts

G.F. Telemann: Viola Concert, LP, Utrechtse Cantorij dir. Maarten Kooi

Bernard van Beurden: Concertante Muziek voor Altviool, Blazers en Slagwerk (1975);

3 maal uitgevoerd: Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam + Radio Opn.

Symfonie Orkest Groningen en Utrecht Symfonie Orkest

Ödöen Partos: Yiskor (In Memoriam), R.K.O dir. Leo Driehuis

Karel Husa: Poem for Viola & Chamber Orchestra, R.K.O dir. Rudolf Krol

Solo werken voor Altviool

G. Kurtag: Signes

Will Eisma: Non-Lecture III 1967

Walter Hekster: Occurence

Sonate’s en korte stukken

Servaes de Koninck: Sonate in D, mmv. Marijke Smit Sibinga (klavecimbel)

G.F. Telemann: Sonate in Bes „

William Flacton; Sonate in C „“

W.F. Bach: Sonate in c, mmv. Marijke Smit Sibinga (klavecimbel)

J. Brahms Sonate in F, mmv. Rudolf Janssen

Stamitz: Sonate in Bes

Hendrik Andiessen: Sonate 1967

Leon Orthel: Sonate op.52

William Keith Rogers: Sonate 1954

Ernst Krenek: Sonate 1953

P. Scharwenka Sonate op.106 in g, mmv. Edith Tangink

Max Vredenburg: Lamento, mmv. Rudolf Janssen

Easley Blackwood: Sonate 1953, mmv. Jan van Vlijmen

Walter Piston: Interludio 1942, mmv. Jan van Vlijmen

Bernard Krol: Lassus Variaties, mmv. Marijke Smit Sibinga (klavecimbel)

Meerdere CD’s met opnamen van Gaudeamus Kwartet en Suonate a Tre

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

English Version:

I am received by Hans Neuburger and his wife Sonja in their pleasant home in Huizen. With a cup of coffee and a pastry, Hans starts to talk about his life and career.

I was born in 1934. During World War 2, my five year younger sister and I were housed in a baptist children’s home in Baarn. Some of the other children had parents who chose to stay behind in the Dutch Indies.

I had violin lessons there already, and travelled by train each Saturday to Amsterdam to have lessons with Ferdinand Helmann, concert master at the Concertgebouw Orchestra. My parents stayed in Amsterdam, apparently one could keep quite anonymous in such a big city. Many years later I heard the the story from a distant cousin of my father: Elie Neuburger, painter, who lived in his 3rd floor atelier on the Snoekjesgracht. The whole neighbourhood knew about it, but kept their mouths shut!

When (during the war) my father could not work as an entertainment musician, my mother, who had a good voice, taught herself some French chansons and German songs, and went to work at the Bar Madrid at the Rokin. The owner of the bar, Heinz Ruf, came to The Netherlands already after 1933. He appeared to have contacts in the resistance, and helped our family a lot.

An incident: During the war, a bald man regularly entered the bar, drank a cognac and then disappeared again quickly. People asked Heinz, “who is that?”, but Heinz always replied: It is better not to ask! After the war the bar re-opened, and the regular customers returned, among them the mysterious bald man. Heinz announced: May I introduce to you: Max Beckmann! (a painter who fled to Amsterdam after speeches against “Entartede Kunst“; he had an atelier at the Amstel. In 1947 he moved to the U.S., where he died in 1970).

I completed my pre-admission coursework and passed my entrance exam for the Conservatory of Amsterdam, back then housed at the Bachstraat. The director of the conservatory, Willem Andriessen (brother of composer Hendrik) said that I could receive a scholarship if I decided to study the viola. From 1951 I studied with Klaas Boon, solo violist of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, in the study track for an Orchestra Diploma.

During my studies, I earned some money by substituting in various amateur orchestras. I also played in the Kunstmaand Orkest, the predecessor of today’s Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra. Their conductor was Karel Mengelberg, a cousin of Willem, composer and music critic in the journal Het Vrije Volk, and vader of Mischa.

After my studies, my father was offered a job in Canada. He didn’t see any future as amusement artist (trumpet and accordeon) in The Netherlands, so our family moved to Winnipeg at the end of 1953. I played in the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, CBC Winnipeg Radio Orchestra, and also the French horn for 3 years in an army orchestra.

After some years it became too provincial for me, and the distances in Canada and the U.S. too large. Fortunately I was able to see a large part of that big country – the expanses of forests and lakes, and even Port Arthur, inside the Polar circle. I also made a journey from Winnipeg to an aunt in Miami with a Greyhound bus, travelling through both countries. In 1955 there were still racial segregation laws in the Southern states of the U.S., and when we passed the famous Mason-Dixon line, I was shocked to see the black passengers moving to the back of the bus.

After six years in Winnipeg, I decided to return to The Netherlands. I found a job in the viola section of the Brabants Orkest. I made acquaintance with Ervín Schiffer (renown viola pedagogue, deceased in 2014) who encouraged me to seek work in a German orchestra.

Finally, after a couple of failed auditions, I won the solo viola job at the Nieder-Sächisches Symfonie Orchester in Hannover. This orchestra played subscription concerts in Hannover and in small theatres in the province, summer concerts in the ballroom of the former Herrenhausen castle (with an open-air stage where G.F. Händel worked in his time). I frequently had a chance to play the Telemann viola concerto, this was easy to program in the small theatres, even without a harpsichord.

In 1963 I auditioned for a solo viola job at the Symphonie Orchester des Bayerische Rundfunk in Munich, and got the 3rd spot. One week earlier, I also auditioned in Hilversum, and was offered the 1st Solo viola job at the Rado Philharmonic (RFO). My erstwhile wife and I agreed that it was less fortunate to let our two children grow up in Germany, so we decided to return to The Netherlands.

Before I started in Hilversum, however, I managed to fall off the stage in Hannover, during a rehearsal. I fortunately had just a fracture in my shoulder blade and a bruised shoulder socket, but the planned Mozart Sinfonia Concertante was out of the question. The fracture healed quickly, so I could start at the RFO on August 15th.

Later I was able to play the Concertante two times with the RFO Concertmaster (Dick de Reus) – once under the baton of Jean Fournet, and later again with Willem van Otterloo.

The first months at the RFO were a kind of extended audition period. I got a go at all the great orchestral solos: H. Berlioz “Damnation de Faust”, A. Ginastera “Variaciones per Orchestra“ op.23, Benjamin Britten “Passacaglia” from Peter Grimes, and with conductor Jean Fournet, also Berlioz “Harold in Italy”.

From Jean Fournet I learned a lot about the French repertoire, such as the differences between e.g. “retenu”, “un peu retenu” and “ritard”, and the his natural way of shaping the works of this repertoire. I have later been annoyed at bad performances of e.g. Fauré’s Pelisande and Ravel’s La Valse. Fournet’s baton technique was very clear and efficient, making even the Sacre (which we played several times with him) easy!

I always found my work at the RFO enjoyable, with a wide repertoire from contemporary to opera and choral works. The Saturday afternoon concerts with great conductors such as Kondrashin, Giulini, Mazur, Haitink, Hans Vonk and David Zinman. From David I got the latest yiddish jokes, which he in turn had learned from Itzhak Perlman.

There were great soloists such as Martha Argerich, Murray Perahia. Earl Wild, J. Bolet and A. Rubinstein. An anecdote: During an early rehearsal at the Concertgebouw, we we found Rubinstein in one of the conductor’s rooms, and we asked, Why are you here so early? You have a concert yourself this evening! He answered, I haven’t heard Martha (Argerich) for such a long time, so I came to listen!

In 1964 I was invited to join the Dutch Oboe Quartet (oboe plus string trio). I made a number of radio recordings with them and played various concerts. The standard fee for a radio recording back then was 85 Guilders, a recital paid 100 and a solo concert was worth 150 Guilders!

In 1969 I was approached by the cellist of the Gaudeamus Quartet, their violist was going on retirement. In those years they still programmed classical repertoire as well as modern music: Bartok 2nd and 4th, Pijper 3rd, Ton de Leeuw, Peter Schat, Lutoslavsky, Luciano Berio, Alban Berg, Anton Webern. This meant that I had to practice a lot, especially in the first year with the quartet, next to all the RFO orchestral works. The Gaudeamus Quartet performed throughout Europe, and twice at the Salzburger Festspiele.

Furthermore, I taught at the Arnhem Conservatory for 10 years: Chamber music, minor viola and methodology. I also served in many examination committees at different conservatories, and I was a jury member at youth competitions and the Charles Hennen Chamber music competition.

Here ends the account of Hans Neuburger. Hans gave me 16 beautiful CD’s with his own recordings of solo works, sonatas and orchestral works. I share with you below the fascinating list of works: well known and lesser known music, but also some pieces that have altogether disappeared from the viola repertoire. Highly recommended as a starting point for the venturous violist!

Concertos and Concertante works:

W.A. Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante K.364 with Dick de Reus, RFO

with cond. Jean Fournet, and idem with cond. W. van Otterloo

Anton Wranitzky: Concerto for 2 violas in C, with Gerard Vermeulen,

RFO, cond. Henk Spruit

Oscar van Hemel: Altvioolconcert, Omroep Orkest dir Henk Spruit

Johann Stamitz: Concerto in C, Kamerorkest P. Hellendaal dir. Henk Spruit

J.Chr. Bach: Concerto per il Pianoforte e Viola obl. in Es, met Rudolf Jansen, RKO dir Paul Hupperts

J.S. Bach: 6e Brandenburgs Concert met Herman Wiegmans, altv; LP, Soester Cantorij dir. Maarten Kooy

H. Berlioz: Harold en Italie, RFO dir. Jean Fournet

Joseph Schubert: Viola Concert in C, RKO dir. P. Hupperts

G.F. Telemann: Viola Concert, LP, Utrechtse Cantorij dir. Maarten Kooi

Bernard van Beurden: Concertante Muziek voor Altviool, Blazers en Slagwerk (1975);

3 maal uitgevoerd: Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam + Radio Opn.

Symfonie Orkest Groningen en Utrecht Symfonie Orkest

Ödöen Partos: Yiskor (In Memoriam), R.K.O dir. Leo Driehuis

Karel Husa: Poem for Viola & Chamber Orchestra, R.K.O dir. Rudolf Krol

Solo works for Viola:

G. Kurtag: Signes

Will Eisma: Non-Lecture III 1967

Walter Hekster: Occurence

Sonatas and Short Pieces:

Servaes de Koninck: Sonata in D, with Marijke Smit Sibinga (harpsichord)

G.F. Telemann: Sonata in Bb „

William Flacton; Sonata in C „“

W.F. Bach: Sonata in c, with Marijke Smit Sibinga (harpsichord)

J. Brahms Sonata in F, with Rudolf Janssen

Stamitz: Sonata in Bb

Hendrik Andiessen: Sonata 1967

Leon Orthel: Sonata op.52

William Keith Rogers: Sonata 1954

Ernst Krenek: Sonata 1953

P. Scharwenka Sonata op.106 in g, with Edith Tangink

Max Vredenburg: Lamento, with Rudolf Janssen

Easley Blackwood: Sonata 1953, with Jan van Vlijmen

Walter Piston: Interludio 1942, with Jan van Vlijmen

Bernard Krol: Lassus Variaties, with Marijke Smit Sibinga (harpsichord)

Numerous CD’s with recordings by Gaudeamus Kwartet and Suonate a Tre